Browse

Education

Michigan State University and the Alliance for African Partnership Awarded $895,000 Carnegie Grant

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Michigan State University and the Alliance for African Partnership Awarded $895,000 Carnegie Grant for REIMAGINE Project Advancing Graduate Education and AI in Africa

Michigan State University (East Lansing, Michigan) has been awarded a 36-month, $895,000 grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York under its prestigious Higher Education in Africa program. The grant will support the Alliance for African Partnership (AAP) consortium’s efforts to advance innovative graduate education ecosystems across African universities and to develop a collaborative, transdisciplinary doctoral program focused on artificial intelligence.

The AAP REIMAGINE initiative supports forward-thinking strategies that reshape higher education for the future. Through this investment, AAP—MSU’s flagship platform for equitable and sustainable collaboration with African higher education institutions—will expand its work to strengthen graduate student environments, enhance supervisory and research cultures, and foster institutional systems that enable student success on the continent.

A key component of the project is the development of multiple Artificial Intelligence Doctoral Training Programs, designed to equip a new generation of African scholars with advanced AI expertise, research skills, and leadership capacity. The initiative will leverage MSU’s long-standing partnerships with universities across Africa, ensuring African-led direction, contextual relevance, and sustainability.

“The REIMAGINE Project is fundamentally about examining how doctoral education and research ecosystems across African universities can evolve to better support transdisciplinary scholarship in artificial intelligence,” said Dr. Jose Jackson-Malete, Co-Director of the Alliance for African Partnership and Project Lead for the Carnegie-funded REIMAGINE initiative. “This work is critically needed now. Without intentional investment in doctoral training, supervision systems, and collaborative research environments, Africa risks falling behind in shaping—and benefiting from—the rapid advances in AI that are already transforming societies and economies worldwide.”

Over the next three years, the project will:

Review and strengthen policies for graduate student mentorship, supervision, and research environments across AAP member institutions.

Support institutional innovations that promote student well-being, academic success, and professional development.

Launch a continentally grounded transdisciplinary doctoral program focused on artificial intelligence, expanding access to emerging fields that drive economic and societal transformation.

Foster deeper collaboration between MSU scholars and African research teams through joint programs, co-created curricula, and capacity-building initiatives.

Since its inception in 2016, AAP has worked across the consortium and beyond to promote equitable partnerships, research excellence, and sustainable development solutions. This new investment from Carnegie marks a pivotal milestone in scaling AAP’s impact on higher education transformation.

About the Alliance for African Partnership (AAP) AAP is a consortium convened by Michigan State University to promote collaborative, transdisciplinary partnerships among 10 member African institutions, MSU, and global stakeholders. The Alliance focuses on building capacity, supporting innovation, and advancing shared research priorities that address global challenges.

About the Carnegie Corporation of New York Founded in 1911 by Andrew Carnegie, the Carnegie Corporation of New York is one of America’s oldest philanthropic foundations focused on advancing knowledge and understanding through grants in education, strengthening U.S. Democracy, international peace and security, and higher education in Africa, supporting initiatives that promote civic engagement, reduce polarization, and foster global cooperation, continuing Carnegie's legacy of social progress. The REIMAGINE program supports bold, future-focused approaches to revitalizing higher education and strengthening global knowledge systems.

By:

Baboki Gaolaolwe-Major

Thursday, Jan 22, 2026

YOUTH EMPOWERMENT

+2

No Preview Available

Leave a comment

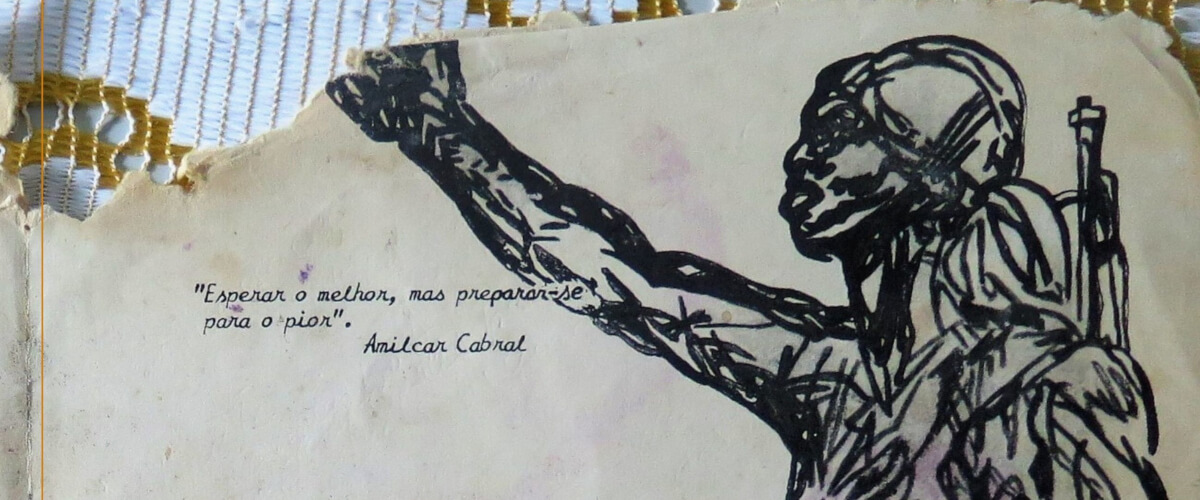

The Alter-Lives of Independence Movements: Frustrated Hopes, Renewed Utopias

Carmina UntalanLocationPortugalDecades after formal decolonisation, anti-colonialism and anti-imperialism have remained a wellspring of inspiration and contestation. Studies about anticolonial thought, the 1955 Bandung Conference, and transcontinental solidarity movements have proliferated in academia and activist networks, providing the basis of theories and practices of resistance in contemporary times. Nevertheless, the ideas and the movements they inspired did not perish with the epoch that produced them. They evolved and acquired alternative lives in the period of nation-building and world-making, whether in extended or distorted forms. On the one hand, there were local and transnational efforts to sustain and enrich the revolutionary impulse through embracing the anticolonial spirit in various areas such as development, education, and diplomacy. As international institutions such as the UN welcome additional member states, Europeans and non-Europeans travelled to decolonised states like Algeria and Angola to learn and further cultivate ideas in building new societies. On the other hand, some dominant groups that took over the independent states capitalised on the anti-colonial pride to justify authoritarian and anti-democratic rule. Their utopian visions led to the systematic oppression of opposing forces and reproduced the hierarchical international state model. The fear of neocolonialism and disillusionment propelled both the former coloniser and colonised to reorganise their strategies and desires in the face of an emerging world order.

This two-day conference on the alter-lives of independence movements explores the evolution and transformation of anti-colonial and anti-imperial struggles. It focuses on the events and reflections about the early years of independence, a period of turbulent transition from colonial domination to self-governing nation-states, and of tumultuous beginnings of a new international order. We introduce the concept “alter-lives” to denote the process of altering imaginaries and practices that emerged during the colonial period in responding to uncertain futures, including the political uses of anticolonial memories and/or histories. It also refers to alternative relations forged between and among the former colonisers and colonised after independence. Thus, using “alter-lives” as a conceptual ground, this conference engages in the following questions: first, how have anticolonial thinking and practices evolved domestically and transnationally? Second, what were the structural and agential forces behind these evolutions? Third, how were anticolonial memories and histories politicised to achieve certain ends? Fourth, what difficulties did these agents face in realising their envisioned future? Lastly, how have alterations and alternatives affirmed and/or challenged the revolutionary ideas of the independence struggles?

We welcome theoretical and praxis-oriented proposals to gather scholars, activists, and artists from various disciplinary backgrounds and acquire a broad comparative perspective. Possibleareas include, but are not limited to:

Transnational solidarities and resistance, such as North-South and South-South cooperation

Nation-building

Anticolonial thought and figures

Diplomacy and international affairs

Pedagogy and knowledge transmission

Literary and artistic representations, such as documentaries, films, and novels

Rhetorics of failure, frustrated political projects

Please submit your abstract (300 words max.) by 13 February 2026 to jiw.hopesandfears@gmail.com.

Decisions will be communicated by the first week of March 2026.

Contact Email

jiw.hopesandfears@gmail.com

URL

https://ihc.fcsh.unl.pt/en/events/alterlives-independence-movements/?fbclid=IwY…

Attachments

CfP Poster Alterlives

By:

Aaron Dorner

Tuesday, Jan 13, 2026

CULTURE AND SOCIETY

+1

No Preview Available

Leave a comment

Africa Global Partnership Scholars

In an era where complex global challenges demand collective action, the need for international collaboration and knowledge sharing has never been more critical. Africa Global Partnership Scholars Program (Africa GPS) is a cohort-based program, designed for early to mid-career MSU faculty to create and deepen new scholarly partnerships with collaborators and peer institutions in Africa in support of MSU’s global mission.

PROGRAM OBJECTIVES:

Foster the development of a group of faculty members dedicated to establishing and enhancing international research connections, collaborating on solutions with African partners, and adopting a global perspective in their scholarly work

Support MSU’s 2030 strategic plan goal of discovery, creativity and innovation for excellence and global impact

Connect MSU faculty with potential collaborators and mentors in Africa, expand the scholars' international networks, and offer support for establishing long-lasting collaborations

Heighten global awareness and research dialogue

Elevate the status of MSU’s global mission

Capitalize on opportunities to leverage external resources and form partnerships

ELIGIBILITY FOR APPLICATION

Tenure-stream or fixed term faculty at Michigan State University without prior scholarly experience in Africa are eligible to apply for Africa GPS.

REQUIRED APPLICATION MATERIALS

As part of the application process, the applicant must submit the following materials:

Completed application questionnaire

An up-to-date curriculum vitae (max 4 pages)

A one-page statement that describes your reasons for applying, potential research focus, and if known, the AAP consortium institution and African country of interest for the collaboration. If needed, AAP can help identify the country, mentor and/or the collaboration partner based on the applicant’s interests.

A letter expressing strong support from the Chair/School Director/Dean. The letter should affirm:

The candidate’s international interest, experience, and/or research

The candidate’s strengths as a researcher within the context of unit expectations

The candidate’s proposed project will advance the mission and goals of the academic unit, be supported by the unit, and benefit international partners

Applicants are encouraged to obtain a commitment from their unit or college to provide a 20% cost share. While cost sharing is not required, preference will be given to proposals that include this match.

FUNDING

To facilitate the participation of faculty members selected as Africa GPS Fellows, AAP will provide support for the following:

Up to $10,000 in support of international travel and scholarly collaborations with a researcher and/or mentor at an AAP Consortium member institution. The $10,000 may be used to support the MSU faculty members’ individual travel, collaborative research activities or to bring an African partner to MSU.

Connection with potential collaborators, mentors, and institutions in Africa

Structured workshops on establishing and navigating international partnerships

Financial Guidelines:

The financial support must be expended prior to the end of the program (one year after awarded).

Preference will be given to applicants who provide a 20% match from the applicant’s unit, department or college.

PROGRAM EXPECTATIONS

Africa GPS participants are expected to develop a sustainable collaboration with peer researchers at an AAP consortium institution. As a result, within two years of being selected for the program, the scholar is expected to achieve the following outputs:

A collaborative research paper coauthored with their African collaborator to be submitted for publication.

A concept note of a proposal submitted to a funding agency to sustain the partnership with the African collaborator.

Progress reports submitted every six months to AAP documenting how the collaboration is progressing and any challenges that may have arisen.

Attend program orientation, professional development workshops organized by AAP, and other relevant events as shared by the AAP team.

SELECTION CRITERIA FOR GLOBAL RESEARCH FELLOWS

The criteria below will be utilized to evaluate candidates for their selection to the Africa GPS program:

Commitment Level: Applicants need to show a readiness to dedicate the necessary time to maximize the benefits of the Fellowship year, along with a proven scholarly potential that supports such a commitment.

Research Interest: Candidates should demonstrate a strong commitment to international research and articulate how participation in Africa GPS will contribute to their personal and professional development

Unit Support: Candidates must have strong support from relevant departmental or school and college administrators, indicated by enthusiastic recommendations.

Alignment of Interests: The applicant’s international research interests should align with the Africa GPS’s mission to foster excellence in international research.

Apply here: https://msu.co1.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_bIS1j4JJxUE2voq

SELECTION OF FELLOWS

Applications are due by January 30, 2026. Application materials will be reviewed by a selection committee in International Studies and Programs. Scholars will be announced by May 2026. Funds must be transferred to selected scholars by June 30, 2026.

If you have any questions, please contact Justin Rabineau at: rabinea1@msu.edu

By:

Justin Rabineau

Monday, Dec 22, 2025

AGRI-FOOD SYSTEMS

+6

Leave a comment

AAP Global Engagement Fund Support Arts-Based Youth Research and Engagement

When photographer and educator Prof. Peter Glendinning of Michigan State University returned to South Africa this September, his goal went far beyond presenting artwork. Supported by the Alliance for African Partnership (AAP) Global Engagement Fund (GEF), Glendinning traveled to Johannesburg and Cape Town to advance a collaborative, arts-driven research initiative that is reshaping how youth experiences are documented and understood across Africa. For years, Glendinning has been developing Attached to the Soil, a project that pairs portrait photography with metaphor and narrative to explore young people’s aspirations, challenges, and identities. What began as a 2019 Fulbright project in South Africa has evolved—through sustained partnership—into a model for how the arts can generate meaningful social insight. This work aligns directly with AAP’s culture & society priority area, which supports projects that use cultural expression to address complex societal issues.

Strengthening a Continental Research Partnership

During his visit, Glendinning met with partners at University of Pretoria, one of AAP’s 12 member institutions, including Prof. Zitha Mokomane, a professor in the Department of Sociology and Deputy Dean for Teaching and Learning in the Faculty of Humanities, who has been conducting sociological analysis of the project’s original youth-created images and stories. The findings point to recurring themes: belonging, hope, fear, opportunity, and the persistence of socio-economic barriers.

With support from the Global Engagement Fund, the partners spent their time together outlining the next phase of the work—a potential 2027 pan-African expansion that could engage youth from multiple institutions and countries. The goal is to create one of the most comprehensive collections of narrative and visual data on African youth aspirations to date.

“The dataset we envision would allow us to compare experiences across countries, contexts, and cultures, using the arts as a bridge,” Glendinning explained. The in-person meetings made possible by the GEF award were essential for refining the research design, establishing a shared methodological framework, and preparing for future proposal development.

Cultural Institutions as Crucial Partners

Glendinning’s work emphasizes not only the creation of new cultural materials but also the preservation of Africa’s photographic heritage. While in Johannesburg, he met with leaders at the Bensusan Museum of Photography to advance efforts to secure funding for preserving its internationally significant collection of historic photographic equipment and images. He also held discussions at the Nelson Mandela Foundation, which held an 8-month exhibit of the project in 2023, exploring how youth-generated narratives from Attached to the Soil could contribute to public memory and civic learning through the foundation’s ongoing partnership. These engagements expand the project’s reach beyond academia and into community and heritage spaces—an approach deeply aligned with AAP’s focus on research for broader impact.

Festival Participation Amplifies Youth Perspectives

Glendinning’s work also reached public audiences during the inaugural Cape Town Photography Festival, where Attached to the Soil opened as an exhibition at the Simon’s Town Museum. The festival setting provided a platform for deeper conversation around the project’s themes. During a public dialogue, Glendinning and Malissa Louw, one of the original participants, spoke about the creative process and the realities behind the images—drawing attention to the power of youth storytelling as a form of social documentation.

He also led two workshops: a digital photography master-class for community members and a session for 40 students at the Cape Peninsula University of Technology. Both emphasized photography as a tool for reflection, empowerment, and evidence-gathering—illustrating how artistic training can support community insight and youth leadership.

A Model for Arts-Driven, Partnership-Based Research

Following the festival, Glendinning continued planning with Prof. Mokomane during her September visit to Michigan State University, which was also supported by the GEF. Together, they are refining the concept for the multi-country expansion and identifying ways for AAP partners to contribute to the next phase.

For AAP, Glendinning’s and project and his partnership with Mokomane exemplify the role arts and culture can play in addressing societal challenges: by elevating local narratives, strengthening community connections, and deepening understanding across diverse contexts. The Global Engagement Fund is central to this impact—making it possible for faculty like Glendinning to build the relationships and shared vision that long-term, equitable partnerships require.

As plans move forward, Attached to the Soil will offer youth across the continent the chance to tell their stories—and help researchers, educators, and communities better understand the world through their eyes.

By:

Baboki Gaolaolwe-Major

Monday, Dec 15, 2025

CULTURE AND SOCIETY

+2

Leave a comment

AAP Steps Up Its Global Footprint at Falling Walls 2025

The Alliance for African Partnership (AAP) strengthened its global visibility this year with a significantly expanded presence at the Falling Walls Summit in Berlin, signaling a new phase in Africa’s engagement with one of the world’s leading platforms for science, innovation, and societal impact.

The momentum follows a fast-growing collaboration between AAP and the Falling Walls Foundation, an alliance that has already produced tangible results. LUANAR in Malawi became the first institution in the consortium to launch a combined Falling Walls Engage and Lab, followed by the University of Botswana, which introduced the Gaborone Lab in 2025 and is preparing to roll out the Engage program in 2026. For AAP, these developments are more than individual wins: they mark the beginning of a wider rollout across the consortium, designed to strengthen research communication and create a more connected science engagement ecosystem across Africa.

At this year’s Summit, AAP member universities made their strongest showing yet. Lab winners from LUANAR and the University of Botswana took the stage in Berlin, showcasing African innovation to an international audience of scientists, investors, policymakers, and global media. Senior leaders from across the consortium also attended, led by Michigan State University’s Vice-Provost for International Studies and Programs, Professor Titus Awokuse.

During the delegation meeting with Falling Walls’ Executive Director, Andreas Kosmider, there was clear enthusiasm about the trajectory of the partnership. Discussions focused on deepening African participation in next year’s Summit and widening the circle of collaborators to include government ministries, policymakers, and funding agencies, an effort aimed at opening new channels for African–German cooperation.

For AAP, the stakes are high. Strengthening research communication equips young African scientists to tell their stories compellingly, improving public understanding and increasing the influence of research on policy. The Labs, meanwhile, function as early-stage innovation pipelines, giving African entrepreneurs exposure, mentorship, and a global platform for emerging ideas. The partnership also enhances institutional visibility, positioning African universities as active players in global science diplomacy.

Planning has already begun for next year’s Summit, with AAP leaders working on a coordinated roadmap to ensure a more visible and more diverse African presence in 2026. The goal is not simply to attend, but to shape the agenda by bringing African voices, research, and innovation to the centre of the global conversation.

As AAP expands its Falling Walls footprint, the partnership is beginning to look less like a program and more like an ecosystem-building catalyst. It is strengthening the consortium internally, opening new possibilities externally, and giving African researchers and innovators a much-needed global stage. And if the early signs are anything to go by, the walls separating African science from global visibility are starting to crack, making space for a new era of collaboration and opportunity.

By:

Baboki Gaolaolwe-Major

Thursday, Dec 11, 2025

CULTURE AND SOCIETY

+3

Leave a comment

Call for Papers: History of Technology Conference

“Engaging the History of Technology”

International Congress of History of Science and Technology

Annual Meeting

Democritus University of Thrace

Alexandroupolis, Greece

October 8 – 11, 2026

The theme of this conference, “Engaging the History of Technology”, invites critical reflections on how history of technology can engage with evolving methodologies, theories and pedagogies, and other branches of historical study to demonstrate that understanding technologies’ pasts are essential to navigating contemporary challenges. The conference, therefore, seeks contributions across spatial and epistemic boundaries: from the everyday and local to the geopolitical and planetary; from archival practice to classroom teaching and public engagement; and from discipline-specific research methods to interdisciplinary collaborations.

Contributors may engage with one or more of the following themes, or even suggest new ways of thinking about:

1. The History of Technology between the Local, the Regional, and the Global:• Circulation of technologies, expertise, and knowledge across borders• Adaptation and appropriation of technologies in different cultural contexts• Tensions between globalisation and localisation in technological change• Regional networks and their role in shaping technological trajectories• Colonial, postcolonial and decolonial dimensions of technology• Networks of maintenance and repair2. History of Technology, Historiography and Education:• Methodological innovations in researching the history of technology• Interdisciplinary approaches and their challenges• Teaching the history of technology in universities and schools• Public engagement and the communication of technological history• The relevance of technology history to contemporary policy debates• Digital humanities and new forms of historical scholarship3. Intersections between the History of Technology and Other Fields of Historical Study:• Technology and social history: class, labour, gender, and everyday life• Technology and cultural history: representation, identity, and meaning• Technology and environmental history: sustainability, resource use, and ecological change• Technology and economic history: innovation, industrialisation, and development• Technology and political history: governance, regulation, and power• Technology and the history of medicine: cultural values, therapeutic practice, and material conceptions about the human body4. Special Focus: Museums, Material and Intangible Cultural Heritage, and Public Engagement: Given our collaboration with the Ethnological Museum of Thrace, the planners particularly welcome proposals that engage with material and intangible culture, museum practices, and public history. They are interested in innovative session formats that:• Explore tensions and synergies between academic and museum approaches to technological history• Demonstrate object-based learning methodologies• Address the challenges of communicating technological history to diverse publics• Examine the role of museums in preserving and interpreting technological heritage• Study visitor engagements with intangible heritage, particularly those of marginalised and silenced ethno-cultural communities• Critically examine the funding relationships between private technological and industrial interests, and museum

Proposals will be accepted in the following formats:

Paper presentations

Individual and author teams’ presentations.Please, submit an abstract of up to 350 words.

Panel Sessions

Thematically coherent sessions of 3-4 papers. Panel organisers should submit a panel abstract (up to 400 words) describing the theme and its significance; after approval the conference committee and the panel organisers will issue a specific call for proposals (individual or author teams’ paper abstracts up to 350 words each).

Roundtables

Discussion-based sessions with 4-6 participants addressing a specific question or debate. Organisers should submit a description of the topic and format (up to 350 words); names and brief bios of participants (up to 100 words each); key questions to be addressed.

Graduate Student and Early Career Opportunities

ICOHTEC is committed to supporting emerging scholars. We particularly welcome submissions from graduate students and early career researchers. The conference will feature:• Visual Lightning Talk Competitions for graduate students• Mentorship opportunities pairing students with established scholars• Book development workshops

Submissions of abstracts through the conference website: December 15, 2025 - January 31, 2026

Official conferencewebsite: https://icohtec2026.hs.duth.gr

- Peter Alegi, MSU Department of History -“Soccer as Work and Play: A Congolese Life Story, from Colonialism to Globalization” (co-sponsored by the MSU Department of African American and African Studies and the MSU African Studies Center)

Monday, March 23 - Jenelle Thelen – “Smooth as Silk: Working Women of the Belding, MI Silk Mills (1902-1908)” (co-sponsored by the MSU Center for Gender in Global Context)

Friday, April 3 - David Stowe, MSU Religious Studies – “The Musical Tanner: Negotiating Work, Music, and Belief in Revolutionary Boston”

* TBD - Nicholas Sly, MSU Department of History - “Curing the Crisis of Masculinity: Calisthenics and Office Work in the Early Twentieth Century”

Check out all the Our Daily Work/Our Daily Lives brown bag presentation recordings available on the MSU Library website (over 125 and still counting!!- JPB)

Did you miss a brown bag presentation that you really want to hear? Or perhaps you may want to explore the listing of past presentations that you didn't even know about. There's an answer to both quests.

Thanks to all our friends at MSU Vincent Voice Library, there is a new home for all our recorded brown bags. Follow these links and you should be able to tap into all of the recordings we have cataloged thus far: Our Daily Work/Our Daily Lives Channel or https://mediaspace.msu.edu/channel/channelid/209060293. Easy Peasy!! Thanks to everyone for setting us up this way!!!

The deepest note of Thanks to all of the folks at the Vincent Voice Library who have worked with us to create this archived set of recordings. Thanks to Shawn, James, Mike, Rick and the late John Shaw for their work over the years on our behalf.

For over thirty years, "Our Daily Work/ Our Daily Lives" has been a cooperative project of the Michigan Traditional Arts Program and the Labor Education Program.

By:

Aaron Dorner

Thursday, Dec 4, 2025

CULTURE AND SOCIETY

+1

No Preview Available

Leave a comment

Student Research Fellowship

The Alliance for African Partnership (AAP) and the MSU African Studies Center (ASC) are pleased to announce our Student Research Fellowship. This award supports:

MSU graduate students’ travel to any African country for research.

Graduate students from AAP’s ten African consortium members to travel to MSU for research.

MSU graduate students’ travel in the U.S. to present their research on Africa at an academic conference.

AAP and ASC recognize that graduate students may have limited opportunities to apply for grants and fellowships to conduct international research and to access funds for conference travel to disseminate their research results. To address this issue, AAP and ASC have established the Student Research Fellowship.

Funding

Each research fellowship will be up to $2,000, awarded for travel and/or fieldwork expenses.

Each conference travel fellowship will be up to $1,000 and will be on a reimbursable basis.

Applicants for research and conference travel fellowships should specify all other funding sources, if applicable.

For students from AAP consortium members, funds will be provided to the MSU host faculty member to pay for travel costs directly.

For students from MSU, funds will be provided either via the home department or via another method; AAP and ASC will work with students on a case-by-case basis on fund transfer.

Eligibility

All applicants must be graduate students currently enrolled in a degree-granting program at one of AAP’s ten African university consortium members or at MSU.

MSU applicants for research funds must secure affiliation with an African university, institution, or organization for the time in which they will conduct their research and in the country to which they are traveling.

Applicants from the ten AAP African university consortium members must be supervised by an academic at their home institution who is collaborating with an MSU faculty member. The student must be hosted by the MSU faculty member/department.

All applicants for research funds must complete their university requirements related to doing research (e.g., approved research plans, ethical conduct of research (or IRB) training and approvals, etc.).

All fellowship recipients must return to their home university as registered students in the semester or term following the award.

All fellowship recipients must be in good academic standing, and priority will be given to underrepresented students and those with demonstrated financial need.

All fellowship recipients must write and submit a report (3 to 5 pages) on their research and experiences within one month of their return from the research trip or conference travel. The report template will be provided to students upon their award.

To learn more about the program, including how to apply, visit:https://aap.isp.msu.edu/funding/student-research-fellowship/

By:

Baboki Gaolaolwe-Major

Tuesday, Nov 18, 2025

EDUCATION

No Preview Available

Leave a comment

Faculty Global Engagement Fund

AAP is pleased to announce that the Faculty Global Engagement Fund is now available to Michigan State University (MSU) faculty members conducting research in Africa. This fund is designed to support:

Collaborative research travel

Conference/workshop travel

Capacity-building and training travel

This fund supports MSU faculty members in strengthening and developing collaborative partnerships with African institutions through strategic travel. AAP seeks to help faculty maintain momentum in their research endeavors and international collaborations by providing travel support to engage with African partner institutions and/or to present their research at conferences or other public forums.

For travel and/or fieldwork expenses: $5,000.

For international conference travel: $5,000

For domestic conference travel: $1,000

Applications are accepted on a rolling basis through May 31, 2026, subject to funding availability. The application process may close early if all funds are awarded before May 31, 2026. All funding must be transferred to recipients by June 13, 2026.

To learn more about the program, including how to apply, visit:https://aap.isp.msu.edu/funding/faculty-global-engagement-fund/

By:

Baboki Gaolaolwe-Major

Tuesday, Nov 18, 2025

EDUCATION

No Preview Available

Leave a comment

Call for Papers Workshop *Africa's Waterways: Technology, Mobility and Skill in a Changing World

The workshop explores Africa’s rivers, lakes, and waterways as vital spaces of transportation, mobility, and exchange—beyond their usual ecological framing. While transport studies in Africa have traditionally focused on roads and vehicles, the human use of waterways is growing with rapid urbanization.

The bilingual (English–French) workshop will examine the technologies, skills, and knowledge tied to waterborne transport across time and regions, emphasizing how these practices sustain livelihoods and adapt to environmental and technological change.

Key themes include:

Transport logistics, ports, and infrastructure.

Mobility practices, safety, and risk management.

Boat building and maintenance traditions.

Propulsion technologies and frugal innovations.

Navigation knowledge and wayfaring.

Multimodal transport networks linking waterways and roads.

River markets and economic activities.

Accidents and shipwrecks.

Environmental change and its impact on mobility.

The workshop aims to foster dialogue between junior and senior researchers and practitioners, building lasting research networks. It is funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) under the Programme Point Sud and will be hosted at Institut Fondamental d’Afrique Noire, Université Cheikh Anta Diop de Dakar. Selected participants will have travel and accommodation covered.

Application deadline: November 3, 2025 (abstract max. 600 words + 2-page CV).

Contact: - Peter Lambertz : peter.lambertz@vub.be

- Valerie Hänsch : valerie.haensch@ethnologie.lmu.de

- Jethron Akallah : jakallah46@gmail.com

- N’Gna Traore : ngnatraore@gmail.com

More information: https://networks.h-net.org/group/announcements/20128477/call-papers-workshop-africas-waterways-technology-mobility-and-skill

By:

Baboki Gaolaolwe-Major

Monday, Oct 20, 2025

EDUCATION

No Preview Available

Leave a comment

African Futures Research Leadership Program - Cohort 6 Call for Applicants

AAP AFRICAN FUTURES RESEARCH LEADERSHIP PROGRAM

Artificial Intelligence in Africa: Transdisciplinary Innovations for Sustainable Futures

Cohort 6 Call for Applicants

Alliance for African Partnership (AAP) invites applications for the sixth cohort of the African Futures Research Leadership Program. This competitive visiting scholar program supports early career researchers from AAP consortium universities to collaborate for one year with faculty members at Michigan State University (MSU) and their home institutions. The program focuses on strengthening skills in impactful research, curriculum development, innovative teaching, scholarly and policy writing, dissemination of research results, and grant proposal development. Scholars will also participate in a structured professional development program while building meaningful and lasting connections with MSU faculty and fellow scholars.

The primary goal of the African Futures Program is to strengthen the capacity of emerging African researchers to become scientific leaders in their communities. The program seeks to foster long-term partnerships with MSU faculty, co-create innovative solutions to Africa’s challenges, and cultivate the next generation of research mentors and leaders.

AAP invites applications from early career researchers to join the upcoming cohort, which will begin virtually in February 2026. Scholars will spend September through December 2026 at MSU for the in-person phase of the program, followed by continued virtual collaboration through early 2027. Each scholar will receive a small grant to support research, teaching, and professional development activities, including conference participation and publication. Scholars will also receive a stipend during their time at MSU, visa support, and round-trip travel from their home institution.

Potential Teaching and Research Areas

The 2026 theme, “Artificial Intelligence in Africa: Transdisciplinary Innovations for Sustainable Futures,” highlights the potential of AI to address Africa’s most critical challenges and opportunities. AI research must be ethical, contextualized, and socially responsible, drawing insights from science, engineering, the arts, business, culture, and society. In addition to thematic research, scholars will contribute to the development of curricula for a transdisciplinary doctoral program in AI in Africa and explore innovations in teaching and learning.

We particularly encourage cross-disciplinary projects exploring AI’s transformative potential in:

Agri-food systems – leveraging AI for food security, sustainable agriculture, and resilient supply chains

Health and nutrition – applying AI in disease prevention, diagnostics, personalized medicine, and strengthening health systems

Climate change, water, energy, and environment – using AI for mitigation, adaptation, monitoring, and sustainable resource management

Ethics, governance, and society – integrating human rights, accountability, and inclusivity in AI design and deployment

Culture and the arts – examining how AI interacts with African languages, creative expression, heritage preservation, and digital storytelling

Engineering and science – developing AI-driven technologies suited to African contexts

Education – enhancing equitable access to learning, bridging digital divides, and improving pedagogy through AI

Business and entrepreneurship – fostering inclusive growth, financial technologies, and youth-led AI innovations to shape Africa’s digital future

Through transdisciplinary collaboration, the program aims to promote AI research and teaching that bridges technical and social disciplines, ensuring innovation reflects Africa’s diverse values and aspirations.

Program Benefits

Professional Development – Structured workshops on equitable partnerships, teaching innovation, academic time management, proposal development, budgeting, and research communication to enhance research, teaching, writing, and leadership skills

Leadership Development – A research leadership retreat focused on building leadership competencies, self-reflection, and career development for research advancement

Collaboration Networks – Each scholar will collaborate with MSU and home institution partners. Collaborators may conduct reciprocal one-week visits. Scholars will also join AAP’s network of researchers at MSU, across Africa, and globally to foster lasting institutional partnerships

Expected Outcomes

By the end of the program, each scholar and their team are expected to achieve at least:

Submission or publication of one to three joint manuscripts

Submission of at least one grant proposal

Presentation at one or more academic or professional conferences

Collaborations are designed to extend beyond the program’s duration. Scholars are encouraged to engage broadly with MSU faculty and maintain partnerships after completion. Participants must submit regular progress reports to AAP and their home institution focal point. Failure to meet program or partnership expectations may result in early termination.

Eligibility

Citizenship in an African country

PhD awarded within the last 10 years

Current employment as Academic Staff at one of the AAP African member universities including Egerton University, Makerere University, University of Dar es Salaam, Lilongwe University of Agriculture and Natural Resources, University of Botswana, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, University Cheikh Anta Diop, Yambo Ouologuem University of Bamako, United States International University-Africa, or University of Pretoria

Official approval of leave or sabbatical for the in-person phase

A home institution partner committed to collaborating throughout the program

Research aligned with the program’s thematic areas, focusing on AI in Africa

Submission of only one proposal per applicant in this round of funding

Application Requirements

An updated CV outlining professional accomplishments

A one-page letter of interest detailing alignment with program priorities, research approach, and potential societal impact

Names of up to three potential MSU faculty collaborators (identified from MSU department websites; applicants should not contact faculty directly—AAP will initiate contact)

Two relevant peer-reviewed publications

Two professional references providing context on the relationship and an assessment of the applicant’s expertise

A one-page letter from the home institution collaborator confirming willingness to participate and travel to MSU for collaboration

A one-page endorsement letter from the Head of Department approving leave

A one-page letter of support from the institution’s AAP Focal Point

Selection Criteria:

Professional merit, scientific ability, and potential for career impact (evaluated through CV, publications, letters, and references)

Institutional assurance of continued employment and support post-fellowship

Commitment to return to the home country after the fellowship

Consideration for diversity across disciplines, institutions, and regions. Priority will be given to projects that demonstrate transdisciplinary approaches integrating technology, culture, ethics, and societal impact

EXTENDED DEADLINE: Applications are due by November 28, 2025

Apply: https://msu.co1.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_eVb2iErQhRpmAPs

For questions, please contact José Jackson-Malete at jacks184@msu.edu or +1-517-884-8587.

This project is made possible with the philanthropic support of Carnegie Corporation of New York

By:

Justin Rabineau

Wednesday, Nov 19, 2025

AGRI-FOOD SYSTEMS

+7

Leave a comment

Short-Term Grants for Women’s Leadership in Peace Processes

Deadline: Dec 31, 2025

Donor: United Nations Women's Peace & Humanitarian Fund

Grant Type: Grant

Grant Size: $10,000 to $100,000

Countries/Regions: Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Angola, Argentina, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Belarus, Belize, Benin, Bhutan, Bolivia, Bosnia And Herzegovina, Botswana, Brazil, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cambodia, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Central African Republic, Chad, China, Colombia, Comoros, Congo (Brazzaville), Congo DR, Costa Rica, Cote DIvoire (Ivory Coast), Cuba, Djibouti, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Egypt, El Salvador, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Fiji, Gabon, Gambia, Georgia, Ghana, Grenada, Guatemala, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, India, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Jamaica, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Kiribati, North Korea, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Lebanon, Lesotho, Liberia, Libya, Macedonia, Madagascar, Malawi, Malaysia, Maldives, Mali, Marshall Islands, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mexico, Micronesia Federated States Of, Moldova Republic Of, Mongolia, Montserrat, Morocco, Mozambique, Burma(Myanmar), Namibia, Nauru, Nepal, Nicaragua, Niger, Nigeria, Niue, Pakistan, Palau, Panama, Papua New Guinea, Paraguay, Peru, Philippines, Rwanda, Saint Helena, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent And The Grenadines, Samoa, Sao Tome And Principe, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Solomon Islands, Somalia, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Suriname, Swaziland, Syria, Tajikistan, Tanzania, Thailand, East Timor (Timor-Leste), Togo, Tokelau, Tonga, Tunisia, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Tuvalu, Uganda, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Vanuatu, Venezuela, Viet Nam, Wallis And Futuna, Yemen, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Montenegro, Serbia, Kosovo, South Sudan

Area: Humanitarian Relief, Leadership, Peace & Conflict Resolution, Women & Gender

The Women’s Peace and Humanitarian Fund (WPHF) Rapid Response Window (RRW) is accepting concept notes from eligible applicants in countries with active peace processes.

For more information, visit https://wphfund.org/rrw-short-term-grants/

Premium Link: https://grants.fundsforngospremium.com/opportunity/op/shortterm-grants-for-womens-leadership-in-peace-processes

By:

Baboki Gaolaolwe-Major

Thursday, Oct 2, 2025

EDUCATION

+1

No Preview Available

Leave a comment

Rapid Response Funding: Direct Support Stream

Deadline: Dec 31, 2025

Donor: United Nations Women's Peace & Humanitarian Fund

Grant Type: Grant

Grant Size: $10,000 to $100,000

Countries/Regions: Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Angola, Argentina, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Belarus, Belize, Benin, Bhutan, Bolivia, Bosnia And Herzegovina, Botswana, Brazil, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cambodia, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Central African Republic, Chad, China, Colombia, Comoros, Congo (Brazzaville), Congo DR, Costa Rica, Cote DIvoire (Ivory Coast), Cuba, Djibouti, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Egypt, El Salvador, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Fiji, Gabon, Gambia, Georgia, Ghana, Grenada, Guatemala, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, India, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Jamaica, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Kiribati, North Korea, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Lebanon, Lesotho, Liberia, Libya, Macedonia, Madagascar, Malawi, Malaysia, Maldives, Mali, Marshall Islands, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mexico, Micronesia Federated States Of, Moldova Republic Of, Mongolia, Montserrat, Morocco, Mozambique, Burma(Myanmar), Namibia, Nauru, Nepal, Nicaragua, Niger, Nigeria, Niue, Pakistan, Palau, Panama, Papua New Guinea, Paraguay, Peru, Philippines, Rwanda, Saint Helena, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent And The Grenadines, Samoa, Sao Tome And Principe, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Solomon Islands, Somalia, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Suriname, Swaziland, Syria, Tajikistan, Tanzania, Thailand, East Timor (Timor-Leste), Togo, Tokelau, Tonga, Tunisia, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Tuvalu, Uganda, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Vanuatu, Venezuela, Viet Nam, Wallis And Futuna, Yemen, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Montenegro, Serbia, Kosovo, South Sudan

Area: Humanitarian Relief, Peace & Conflict Resolution, Women & Gender

The Women’s Peace and Humanitarian Fund (WPHF) Direct Support Stream is accepting concept notes from eligible applicants in countries with active peace processes.

For more information, visit https://wphfund.org/rrw-direct-support/

Premium Link: https://grants.fundsforngospremium.com/opportunity/op/rapid-response-funding-direct-support-stream

By:

Baboki Gaolaolwe-Major

Thursday, Oct 2, 2025

YOUTH EMPOWERMENT

+2

No Preview Available

Leave a comment