Browse

Water, Energy, And The Environment

AAP Global Engagement Fund Support Arts-Based Youth Research and Engagement

When photographer and educator Prof. Peter Glendinning of Michigan State University returned to South Africa this September, his goal went far beyond presenting artwork. Supported by the Alliance for African Partnership (AAP) Global Engagement Fund (GEF), Glendinning traveled to Johannesburg and Cape Town to advance a collaborative, arts-driven research initiative that is reshaping how youth experiences are documented and understood across Africa. For years, Glendinning has been developing Attached to the Soil, a project that pairs portrait photography with metaphor and narrative to explore young people’s aspirations, challenges, and identities. What began as a 2019 Fulbright project in South Africa has evolved—through sustained partnership—into a model for how the arts can generate meaningful social insight. This work aligns directly with AAP’s culture & society priority area, which supports projects that use cultural expression to address complex societal issues.

Strengthening a Continental Research Partnership

During his visit, Glendinning met with partners at University of Pretoria, one of AAP’s 12 member institutions, including Prof. Zitha Mokomane, a professor in the Department of Sociology and Deputy Dean for Teaching and Learning in the Faculty of Humanities, who has been conducting sociological analysis of the project’s original youth-created images and stories. The findings point to recurring themes: belonging, hope, fear, opportunity, and the persistence of socio-economic barriers.

With support from the Global Engagement Fund, the partners spent their time together outlining the next phase of the work—a potential 2027 pan-African expansion that could engage youth from multiple institutions and countries. The goal is to create one of the most comprehensive collections of narrative and visual data on African youth aspirations to date.

“The dataset we envision would allow us to compare experiences across countries, contexts, and cultures, using the arts as a bridge,” Glendinning explained. The in-person meetings made possible by the GEF award were essential for refining the research design, establishing a shared methodological framework, and preparing for future proposal development.

Cultural Institutions as Crucial Partners

Glendinning’s work emphasizes not only the creation of new cultural materials but also the preservation of Africa’s photographic heritage. While in Johannesburg, he met with leaders at the Bensusan Museum of Photography to advance efforts to secure funding for preserving its internationally significant collection of historic photographic equipment and images. He also held discussions at the Nelson Mandela Foundation, which held an 8-month exhibit of the project in 2023, exploring how youth-generated narratives from Attached to the Soil could contribute to public memory and civic learning through the foundation’s ongoing partnership. These engagements expand the project’s reach beyond academia and into community and heritage spaces—an approach deeply aligned with AAP’s focus on research for broader impact.

Festival Participation Amplifies Youth Perspectives

Glendinning’s work also reached public audiences during the inaugural Cape Town Photography Festival, where Attached to the Soil opened as an exhibition at the Simon’s Town Museum. The festival setting provided a platform for deeper conversation around the project’s themes. During a public dialogue, Glendinning and Malissa Louw, one of the original participants, spoke about the creative process and the realities behind the images—drawing attention to the power of youth storytelling as a form of social documentation.

He also led two workshops: a digital photography master-class for community members and a session for 40 students at the Cape Peninsula University of Technology. Both emphasized photography as a tool for reflection, empowerment, and evidence-gathering—illustrating how artistic training can support community insight and youth leadership.

A Model for Arts-Driven, Partnership-Based Research

Following the festival, Glendinning continued planning with Prof. Mokomane during her September visit to Michigan State University, which was also supported by the GEF. Together, they are refining the concept for the multi-country expansion and identifying ways for AAP partners to contribute to the next phase.

For AAP, Glendinning’s and project and his partnership with Mokomane exemplify the role arts and culture can play in addressing societal challenges: by elevating local narratives, strengthening community connections, and deepening understanding across diverse contexts. The Global Engagement Fund is central to this impact—making it possible for faculty like Glendinning to build the relationships and shared vision that long-term, equitable partnerships require.

As plans move forward, Attached to the Soil will offer youth across the continent the chance to tell their stories—and help researchers, educators, and communities better understand the world through their eyes.

By:

Baboki Gaolaolwe-Major

Monday, Dec 15, 2025

CULTURE AND SOCIETY

+2

Leave a comment

African Futures Cohort 5 Arrives at MSU

Alliance for African Partnership (AAP), a consortium of ten leading African universities, Michigan State University (MSU), and a network of African research institutes, is excited to welcome the fifth cohort of the African Futures Research Leadership Program to MSU for the in-person portion of the program. Each early career scholar is paired with a faculty mentor from MSU and their home institution for one year of virtual and in-person collaboration to strengthen research skills, innovations in teaching, writing of scholarly and/or policy publications, dissemination of research results and grant proposals.

A consortium-wide initiative, the African Futures program is designed to strengthen the capacity of a cadre of African researchers to return to their home institutions and become scientific leaders in their community, establish long-term partnerships with MSU faculty, co-create innovative solutions to Africa’s challenges, and in turn become trainers of the next generation of researchers.

African Futures Cohort 5: Alfdaniels Mabingo Performing Arts and Film Makerere University Home Mentor - Sylvia Antonia Nakimera Nannyonga-Tamusuza, Dept of Performing Arts and FilmMSU Mentor – Philip Effiong, Dept of English, Theater Studies & Humanities & Gianina Strother, Dept of African American and African Studies Gladys Gakenia Njoroge Pharmacy Practice and Public Health United States International University – Africa Home Mentor - Calvin A. Omolo, Dept of Pharmacy Practice and Public HealthMSU Mentor - Yuehua Cui, Dept of Statistics and Probability Seynabou Sene Plant Biology University Cheikh Anna Diop Home Mentor - Abdala Gamby Diedhiou, Dept of Plan BiologyMSU Mentor - Lisa Tiemann, Dept of Plant, Soil, and Microbial Sciences Portia T. Loeto Educational Foundations (Gender Studies Section) University of Botswana Home Mentor - Godi Mookode, Dept of SociologyMSU Mentor - Soma Chauduri, Dept of Sociology Betina Lukwambe Aquaculture Technology University of Dar es Salaam Home Mentor – Samwel Mchele Limbu, Dept of AquacultureMSU Mentor - Abigail Bennett, Dept of Fisheries and Wildlife & Maria Claudia Lopez, Dept of Community Sustainability Assilah Agigi Business Management University of PretoriaHome Mentor - Alex Antonites, Dept of Business Management MSU Mentor - Sriram Narayanan, Dept of Supply Chain Management Miriam Nthenya Kyule Agricultural Education and Extension Egerton University Home Mentor - Miriam Karwitha Charimbu, Dept of Crops, Horticulture and Soils MSU Mentor - Susan Wyche, Dept of Media and Information Studies Asha Nalunga Agribusiness and Natural Resource Economics Makerere University Home Mentor - Bernard Bashaasha, Dept of Agribusiness and Natural Resource Economics MSU Mentor - Saweda Liverpool-Tasie, Dept of Agricultural, Food, and Resource Economics

Ezinne Ezepue (participating virtually)Theatre & Film Studies University of Nigeria, Nsukka Home Mentor - Chinenye Amonyeze, Dept of Theatre & Film StudiesMSU Mentor - Jeff Wray, Dept of English

“We were extremely impressed with the quality and diversity of applications we received for this cohort of the African Futures program. We are excited to build on the successes of past cohorts and continue to evolve this program as we support the next generation of African research leaders,” said Jose Jackson-Malete, co-director of the Alliance for African Partnership.

Differing from previous cohorts, Cohort 5 is piloting a hybrid model of the African Futures program. The scholars began their work in February 2025 virtually, then will spend the fall semester at Michigan State University working closely with their MSU mentor. They will then complete the rest of their year back at their home institution, culminating in a research showcase in February 2026 to share the research they’ve done. Partnerships between mentors and mentees are expected to continue beyond the end of the program and lead to sustainable collaboration and future funding opportunities.

For more information, visit the Alliance for African Partnership website

By:

Justin Rabineau

Thursday, Sep 4, 2025

AGRI-FOOD SYSTEMS

+6

Leave a comment

AAP announces 8 new PIRA partnership awards

Alliance for African Partnership (AAP), a consortium of ten leading African universities, Michigan State University (MSU), and a network of African research institutes, is excited to announce the recipients of the 2024 Partnerships for Innovative Research in Africa (PIRA) seed funding. Each team is composed of at least one lead from an AAP African member institution and one MSU lead. Some teams also include additional partners from NGOs and/or other universities from outside of AAP’s consortium. A consortium-wide initiative, PIRA grants are a tiered funding opportunity designed to cultivate and support multidirectional and transregional research partnerships at any stage of their development, whether it be initiatives to explore and create new relationships or scale existing ones. The total amount of PIRA grants awarded in 2024 is over $500,000.

Awarded projects cover diverse disciplinary perspectives and span AAP’s seven priority areas:

Agri-food systems

Water, Energy and Environment

Culture and Society

Youth Empowerment

Education

Health and Nutrition

Science, Technology and Innovation

All projects will integrate gender, equityand and inclusion issues in all stages of the project.

This year’s winning projects include:

Towards the Implementation of Smart Villages in the Rural Communities of Taraba State in Nigeria

Research leads: Shanelle N. Foster (MSU), Chidimma Frances Igboeli (University of Nigeria, Nsukka), Mbika Mutega (University of Johannesburg), Sari Stark (University of Lapland)

Institutional partners: Michigan State University (College of Engineering), University of Nigeria, Nsukka, University of Johannesburg and University of Lapland

Funding tier: Scaling grant (up to $100,000)

Green Technology Extraction and Characterization of Bioactive Components from Edible Fruits of Vitex donania and Uvaria chamae

Research leads: Leslie D. Bourquin (MSU), Insa Seck (UCAD)

Institutional partners: Michigan State University (College of Agriculture & Natural Resources), Universite Cheikh Anta Diop

Funding tier: Planning grant (up to $50,000)

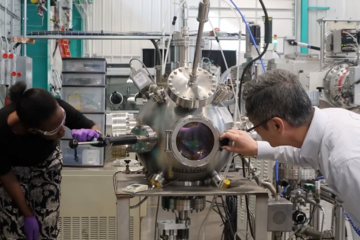

Qi Hua Fan of MSU (left) and Tabitha Amollo of Egerton University (right) working in their solar cell lab.

Develop a Partnership for Renewable Energy Research and Education

Research leads: Qi Hua Fan (MSU), Tabitha Amollo (Egerton)

Institutional partners: Michigan State University (College of Engineering), Egerton University

Funding tier: Scaling grant (up to $100,000)

Bridging the Gap: Strengthening Research, Management and Community Alliances in South Africa’s Largest Coastal Marine Protected Area

Research leads: Amber K. Peters (MSU), Els Vermeulen (UP), Grant Smith (Sharklife)

Institutional partners: Michigan State University (College of Agriculture and Natural Resources), University of Pretoria, Sharklife Conservation Group

Funding tier: Planning grant (up to $50,000)

Changing Public Attitudes and Behaviors of Buying Counterfeits through Evidence-Based Education and Awareness-Raising Campaigns in Kenya

Research leads: Saleem Alhabash (MSU), Maureen Kangu (USIU), Robi Koki Ochieng (USIU), John Akoten (Anti-Counterfeit Authority)

Institutional partners: Michigan State University (College of Communication Arts & Sciences), United States International University-Africa, Anti-Counterfeit Authority

Funding tier: Planning grant (up to $50,000)

Leveraging Tourism and Hospitality Ecosystems to Expand Youth Entrepreneurship and Empowerment in Botswana

Research leads: Karthik Namasivayam (MSU), Mokgogi Lenao (UB)

Institutional partners: Michigan State University (Broad College of Business), University of Botswana

Funding tier: Planning grant (up to $50,000)

Children attending Pre-school in Tanzania benefit from the research project of Bethany Wilinski of MSU and Subilaga M Kejo of University of Dar es Salaam.

Tucheze Pamoja: Co-Creating Feasible and Sustainable Play-based Learning Approaches in Tanzania

Research leads: Bethany Wilinski (MSU), Subilaga M Kejo (UDSM)

Institutional partners: Michigan State University (College of Education), University of Dar es Salaam

Funding tier: Scaling grant (up to $100,000)

Promoting Science Communication and Engagement through Training and Digital Media Platforms

Research leads: Susan McFarlane-Alvarez (MSU), Dikabo Mogopodi (UB)

Institutional partners: Michigan State University (College of Communication Arts and Sciences), University of Botswana

Funding tier: Planning grant (up to $50,000)

“We were extremely impressed with the quality and diversity of proposals we received for this cycle of the PIRA program. The projects that were awarded all embody AAP’s commitment to innovation, equitable partnership, and our shared vision of transforming lives in Africa and beyond,” said Amy Jamison, co-director of the Alliance for African Partnership.

A unique aspect of PIRA grants is the expectation that institutions will establish and develop equitable partnerships from conception to close out of their respective projects. These equitable partnerships will be among the research team members themselves and include relevant local stakeholders. Teams will involve these local stakeholders as appropriate throughout the project, respecting their knowledge and expertise, and taking an adaptive approach that is responsive to the local context.

We invite you to join our virtual PIRA launch and showcase event at 8 a.m., Tuesday, Feb. 25 when all of our awardees will be discussing their projects. You can register for the event on Zoom.For more information, visit the Alliance for African Partnership website.

By:

Justin Rabineau

Monday, Jan 27, 2025

AGRI-FOOD SYSTEMS

+6

Leave a comment

Multidimensional impact of environmental change in the African Great Lakes

Recorded on March 24th, 2023 as part of AAP Public Dialogue Series

By:

Justin Rabineau

Monday, Jan 27, 2025

WATER, ENERGY, AND THE ENVIRONMENT

Leave a comment

Editor's Note: Richard Mkandawire, AAP Africa Director

Dear AAP Members, Stakeholders, Partners and the Public

I am pleased to present the second issue of AAP Connect, focusing on AAP’s strategic goal of research for impact. In this issue, we use the example of a critical theme that lies at the heart of sustainable agriculture and food security in Africa: soil health, fertilizer usage, and agri-food systems. Our inaugural AAP Connect issue published in April, focused on building sustainable networks in research. We wanted to highlight some of the unorthodox approaches to networking, not just the usual meet, and greet, and exchange contacts, but ones that take into account context and timing. If you missed it, please spare some time and browse through it.

We have just returned from Nairobi, Kenya, where African governments led by their heads of state, global donor organizations, and global policy network organizations met at the Africa Fertilizer and Soil Health Summit, 7th to 9th May 2024. At the summit, stakeholders unveiled Africa’s Fertilizer and Soil Health Action Plan and shed light on the pressing need to invest in this plan’s implementation, emphasizing the crucial role of soil health and fertilizer in enhancing food security and nutrition across the continent. This AAP Connect issue, therefore, comes at a critical period where Africa has gone through a challenging period of fertilizer shortages, and governments and global agencies are poised to take action. This aligns perfectly with AAP’s priority area of Agri-food systems, emphasizing one of AAP’s primary Goal 3: Research for Impact, that targets deliver impactful research that transforms lives.

I am also proud to announce to you that witnessing the summit unfolding was a surreal moment for us at AAP because we have played a pivotal role in its conceptualization. It has taken much effort and a lot of back-and-forth negotiations to make it a reality. We are proud to be the technical partner of this important process that will see transformations in Africa’s agri-food systems. The icing on the cake was that we at AAP, in partnership with ANAPRI and top experts in agriculture and soil health from across our consortium, convened a side event that focused on the role of science, research, and training institutions in the realization of Africa’s Fertilizer and Soil Health Action Plan. During this side event, we discussed at length the critical importance of knowledge creation, training, and collaborative research initiatives in driving sustainable soil health and fertilizer practices to improve food baskets in Africa.

Further cementing our commitment to actionable outcomes, AAP collaborated with Catholic Relief Services and the Government of Malawi to host the Malawi Ready event. This event convened key stakeholders to chart a strategic implementation path for Malawi's adoption of the Africa Fertilizer and Soil Health Action Plan. We were honored to welcome the President of Malawi, Dr Lazarus McCarthy Chakwera and other distinguished government officials, signifying the collective resolve to tackle soil health and fertilizer challenges head-on.

For this issue, as a way to spark your minds with innovative approaches to research for impact, we have enlisted top experts to unpack key issues and bring ideas that may be transformed into solutions for Africa. We hope that you will enjoy and be inspired to work on your next impactful research project in agri-food systems or any other field which has the potential to transform lives in Africa and beyond. Together, we can drive meaningful change and pave the way for a more sustainable and food-secure Africa.

Warm regards,

Richard Mkandawire

AAP Africa Office Director

By:

Baboki Gaolaolwe-Major

Wednesday, Jul 10, 2024

WATER, ENERGY, AND THE ENVIRONMENT

+2

Leave a comment

The Role of Science, Institutions of Learning, and Training on Africa’s Fertilizer and Soil Health.

Summary: African soils are in danger, and this crisis threatens to disrupt food security and ecosystems, potentially leading to famine and nutritional challenges. Healthy soil is essential for human existence on earth. Healthy soils have biological, physical and chemical properties found in their top layer, or topsoil, that sustain plant and animal productivity, soil biodiversity and environmental quality.

Healthy topsoil is a key factor in bolstering agriculture productivity in Africa. Yet it is known that African soils are in a crisis. Addressing this urgent issue requires a collaborative effort involving policy and regulation, funding, private and community interventions, and, crucially, the leadership of African research and training institutions. These entities are pivotal in restoring Africa’s soil health and ensuring the appropriate use of fertilizers.

The Africa Fertilizer and Soil Health Summit (AFSHS), held in Nairobi, sought to address these pressing issues. The Summit’s primary goal was to establish an Africa Fertilizer and Soil Health Action Plan, a roadmap designed to tackle the challenges of declining soil health and low fertilizer efficacy across the continent. This plan, envisioned to guide efforts until 2030, aims to enhance agricultural productivity through sustainable practices and robust policy frameworks.

During the Summit, the Alliance for African Partnership (AAP), in collaboration with Michigan State University (MSU) and the Africa Network of Agricultural Policy Research Institutes (ANAPRI), organized a critical side event. This event underscored the indispensable role that African research and training institutions play in shaping and implementing policy reforms for fertilizer and soil health programs.

The Vital Role of African Research and Training Institutions

African research and training institutions are custodians of knowledge and expertise, uniquely positioned to drive sustainable agricultural practices and to address ongoing soil degradation. Their role in promoting sustainable practices and conducting extensive research is central to the success of the Africa Fertilizer and Soil Health Action Plan. These institutions, including universities, scientific crop and livestock institutes, and policy research think tanks, are essential in providing thought leadership, policy engagement, and the development of key solutions and implementation strategies.

Professor Thom S. Jayne of MSU highlighted this during his keynote presentation at the side event. He emphasized that effective implementation of soil health initiatives requires the involvement of trusted local institutions. “The message coming from established local actors will generate much greater trust and commitment than the same message from externally funded outside interests,” he noted. This sentiment reflects a broader recognition that African-led initiatives are crucial for achieving lasting impact and engagement with African governments.

Challenges and Collaborative Efforts

Implementing these initiatives is not without challenges. African food systems face pressures from climate change, population growth, conflict, and land degradation. Innovation is necessary to adapt to these conditions, and this innovation must be driven by robust agricultural research and extension systems. As Thomas Jayne stated, “Innovation is required for African founding populations to survive and remain competitive and productive in the face of all these changes.”

However, the adoption of innovative soil fertility practices among smallholder farmers remains low. Many farmers struggle to consistently implement practices like crop rotations, intercropping legumes, and recycling organic matter. To address this according to Thom Jayne, there must be strong bi-directional learning systems where farmers benefit from new technologies, and scientists understand and address the barriers to adoption.

Path Forward: Empowering Local Institutions

The need for empowering local African institutions will be key to responding to the call implementation of the actions plans. However the local institutions will need to take into account challenges such as; the need for building national coalitions of stakeholders and defining local level coordination mechanisms as well as resources including human and financial These institutions must be supported to fulfill their mandates, drive research and innovation, and implement policies that reflect the realities and needs of African agriculture on the ground. Professor Titus Awokuse from MSU underscored the importance of these partnerships. “Stakeholders must collaborate and contribute to the success of the action plans, from providing leadership and coordination to investing resources and actively participating in the implementation process,” he said. This collaborative approach ensures that the action plans are not just theoretical but are translated into tangible outcomes that benefit farmers and communities across Africa.

Conclusion

The Africa Fertilizer and Soil Health Summit and its associated events highlighted the critical need for a concerted effort to address soil health and fertilizer use in Africa. By leveraging the expertise and leadership of African research and training institutions, supported by a collaborative network of stakeholders, there is a real opportunity to create a more sustainable and productive agricultural future for the continent. The success of these initiatives will not only restore soil health but also enhance food security and resilience, ensuring a prosperous future for Africa and its people. Inherently, this is not a small feat, given the diverse multistakeholder partnerships, alongside the complex nature of various governments, it requires careful navigation. Titus Awokuse reminded everyone that “even though our conversations may take many forms and go in different directions, we need to always remember it's about the people. It's about families, children and individuals that don't have a voice, therefore in our conversations we need to think carefully on how to leverage our positions of privilege to make their voices heard”

By:

Baboki Gaolaolwe-Major

Wednesday, Jul 10, 2024

HEALTH AND NUTRITION

+2

Leave a comment

Malawi Ready: A Transformative Step Towards Soil Health and Agricultural Prosperity

The past month has been surreal for the Alliance for African Partnership (AAP). After years of meticulous planning, we finally witnessed the African Fertilizer and Soil Health Summit in Nairobi. It's been a journey filled with challenges and triumphs. To top it off, we concluded the summit with a post-event organized by AAP, MWAPATA, and Malawian agricultural policy and development institutions under the theme "Malawi Ready."

This event served as a strong message of commitment and reinforcement by the Malawian Government to development partners, affirming that Malawi is fully prepared to implement the Africa Fertilizer and Soil Health Action Plan. His Excellency, Dr. Lazarus McCarthy Chakwera, graced the occasion as the guest of honor for "Malawi Ready."

The Importance of Restoring Soils in Malawi

Malawi, like many other African countries, faces significant challenges related to soil degradation. Soil health is fundamental to agricultural productivity, which in turn is crucial for food security, economic development, and poverty alleviation. Restoring soil fertility in Malawi is not merely an environmental imperative but a socio-economic necessity. Fertile soils lead to better crop yields, improved nutrition, and increased incomes for farmers. This sets off a positive ripple effect throughout communities, enhancing overall well-being and fostering sustainable development.

Government Support and Donor Engagement

Recognizing the critical importance of soil health, the Government of Malawi has taken decisive steps to champion this cause. President Chakwera's presence and endorsement at the "Malawi Ready" event underscore the high level of political will and commitment to this initiative. In his address, President Chakwera emphasized the government's unwavering support for the action plan, highlighting the collaborative efforts required to achieve lasting impact.

The government's role extends beyond endorsement to active engagement with various stakeholders, including donor agencies, private sector partners, and local communities. This multi-faceted approach ensures that the action plan is comprehensive and inclusive, addressing the needs and challenges of all stakeholders involved.

Securing Commitments and Investments

"Malawi Ready" was pivotal in securing commitments and investments from major development partners such as USAID, AFAP, and Catholic Relief Services. These organizations bring financial resources, technical expertise and innovative solutions essential for the successful implementation of the action plan. Their involvement guarantees a robust support system that will drive the initiative forward, ensuring sustainability and scalability.

We are thrilled to have played a central role in driving this initiative forward, led by AAP Director of the Africa Office, Prof. Richard Mkandawire, who also steered the proceedings of "Malawi Ready." The event was marked by fruitful discussions, strategic planning, and a shared vision for a sustainable agricultural future in Malawi.

The Road Ahead

The launch of "Malawi Ready" marks the beginning of a new chapter in Malawi's agricultural development. The focus now shifts to the implementation phase, where the collective efforts of all stakeholders will be crucial. Continuous monitoring, evaluation, and adaptive management will ensure that the initiatives remain aligned with the set goals and objectives. The commitment demonstrated by the Malawian Government, along with the support from international partners, sets a strong foundation for success. Together, we aim to transform Malawi's agricultural landscape, restore soil health, and create a resilient and prosperous future for its people.

In conclusion, "Malawi Ready" is not just a campaign; it is a clarion call to action. It embodies the hope and determination of a nation ready to reclaim its soil health and agricultural productivity. As we move forward, let us remember that the journey to sustainable development is a collective one, and with unity and perseverance, we can achieve remarkable milestones for Malawi and beyond.

By:

Baboki Gaolaolwe-Major

Wednesday, Jul 10, 2024

WATER, ENERGY, AND THE ENVIRONMENT

+1

Leave a comment

Nourishing the Future: Reflections on the Follow-up to the African Fertilizer and Soil Health Summit

Summary: In the wake of Africa's escalating food security crisis, marked by chronic undernourishment and stunted growth in children, a transformative approach to fertilizer use and soil health is paramount. Despite past efforts like the Abuja Declaration, fertilizer usage in Africa remains critically low, contributing to poor crop yields and persistent hunger. The recent African Fertilizer and Soil Health Summit has reignited hope with a comprehensive Action Plan aimed at integrating fertilizer use with sustainable soil health practices. This article delves into the necessity of deep and hyper-localization in policy and practice, advocating for tailored, evidence-based approaches to boost agricultural productivity. 12 is Professor in Michigan State University’s Department of Agricultural, Food, and Resource Economics (AFRE), Senior Co-Director of AFRE’s Food Security Group (FSG), and Director of the Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Food Security Policy Research, Capacity, and Influence (PRCI) funded by USAID

A cursory glance at the latest data on “Africa’s food and nutrition” reveals a grim reality: hundreds of millions are undernourished. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), over 282 million Africans are chronically undernourished—a number exacerbated by the back-to-back effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war, which have added tens of millions to this tally. The continent’s food security crisis is further underscored by the fact that over a billion people cannot afford a healthy diet, with children disproportionately affected; approximately 30% of African children are stunted due to malnutrition.

The fundamental driver of this crisis is the widespread poverty that makes so many unable to obtain the food they need, whether through their own production or through the market. Yet there is no question that the continent's inadequate food production capabilities, and the failure of these capacities to keep up with population growth, is a major contributor to the crisis. A significant factor in this inadequate and slowing growing production capacity is low use of fertilizers and the poor health of soils across Africa. Compared to other regions, African countries use minimal amounts of fertilizer, resulting in lower crop yields and perpetuating cycles of hunger and malnutrition.

In recognition of this fact, and under the auspices of the African Union, the African continent just held a successful African Fertilizer and Soil Health Summit (AFSHS) in Nairobi. Featuring wide attendance of political and food systems leaders across the continent together with development partners, the Summit captured and fueled their commitment and enthusiasm to improve the lives of African farmers and consumers. A key contribution of the Summit was to harness this commitment to an Action Plan that provides a strong basis for addressing the continent’s longstanding agricultural productivity crisis. A major reason that Summit participants emerged optimistic of progress is the specificity of the continental Action Plan and its understanding that fertilizer, if it is to drive sustainable intensification, must be integrated into a broad package of reformed policies and programs focused on soil health.

Yet we have been here before. The Abuja Declaration on Fertilizer for the African Green Revolution, signed by 14 African heads of state and released during the African Fertilizer Summit of 2006, set lofty goals for increased fertilizer use and productivity growth on the continent. Yet results have been disappointing at best. On the one hand, fertilizer use per hectare (ha) of arable land has grown 79% since 2006, nearly double the growth rate of South Asia, comparable to the rate in Latin America and the Caribbean, and vastly higher than East Asia’s growth of only 8%. Yet this growth cannot be considered surprising since it started from an extremely low base; the result is that levels of fertilizer use in Sub-Saharan Africa today remain a small fraction of those in any other region of the world – 23 kg/ha compared to 207 kg/ha, 187 kg/ha, and 312 kg/ha, respectively, in Latin America and the Caribbean, South Asia, and East Asia (World Bank Databank). And use today is less than half the target of 50 kg/ha that the Abuja Declaration set for 2015. Regarding productivity, while cereal yields nearly doubled from 2006 to now, this growth is less than half that achieved in every other region of the developing world during this time. This means that African agricultural productivity has fallen even further behind the rest of the world since Abuja.

The message is clear – Africa needed a big push to do major catch-up growth in fertilizer use, soil management, and yields, and failed to achieve it. Partly as a result, after at least two decades of declining hunger and malnutrition, both have been on the rise on the continent in recent years.

What needs to be different this time?

A useful lesson in life and in work is that one should not expect different results while continuing to do what we’ve done in the past. This lesson can be hard to learn, especially for the large bureaucracies – governments, large bilateral and multilateral development partners, and even the international agricultural research community - that are central to generating a productive response to the 2024 AFSHS. So, what needs to change if we want, this time, to see the kind of transformational change that is needed in Africa’s agricultural production practices if the continent is to sustainably nourish its population and pull its people out of poverty?

This note suggests that obtaining different results this time – achieving sustained and effective action for improved fertilizer use and soil health - requires a much more profound localization of approach, and that this localization requires important changes in how governments, their development partners, and other stakeholders behave. Specifically, we argue for two different but complementary approaches: deep localization in the process of policy and programmatic design and in how research to support that process is conceived and carried out; and what some call hyper localization in technical recommendations for farmer practices on their fields. These two ideas – deep localization and hyper localization - need to be brought together to reinforce each other and jointly drive the design and implementation of a new and much more effective generation of policies and programs to achieve rapid and sustained growth in African agricultural productivity

The rest of this note explains what we mean by deep localization and hyper localization, why we believe that they need to go hand-in-hand in the follow-up to the AFSHS, and what they imply about how governments and development partners, including applied researchers in the global north and global south, need to change the attitudes and approach they bring to their work.

Hyper Localization

Hyper-localization is a popularized term that refers to the scientific concept of “4R” in soil nutrient management – right source, right rate, right time, and right place (Fixen, 2020; Reetz et al., 2015). The messages is that one needs to apply the right kind of nutrient in the right formulation and needs to apply it at the right rate and at the appropriate time, based on the specific field receiving the nutrient. Hyper-localization thus refers to the technical aspects of nutrient use and emphasizes customization to a farmer’s specific field. We offer four comments in this regard.

First, localized fertilizer recommendations are important across the world, since soil characteristics can vary quite a lot across countries, across regions in a country, across fields, and even within a field. The rapid rise of “precision agriculture” in industrialized countries, in which a digital soil map of a farmer’s field linked to GPS technology that varies the blend applied by the machinery to match the soil map, is a clear indicator of the importance of highly localized fertilizer use to farmer profitability.

Second, much more localized application may be especially important in Africa, since this continent seems to present substantially higher variability over space in soil characteristics than other regions of the world (Suri and Udry, 2022). Together with large variability over space in transport infrastructure, crop and fertilizer prices, and access to markets, this agroecological heterogeneity drives extremely large variation in returns to fertilizer (Suri, 2011).

Third, fertilizer policy in Africa has failed to come to terms with this heterogeneity through its decades-long “one-size-fits-all” approach. Too often, a sharply limited set of fertilizer formulations is provided nationally, often through government programs at subsidized prices. Given the heterogeneity just discussed, this is a recipe for poor profitability and low farmer adoption despite very high programmatic expenditures.

Fourth, implementing a 4R approach – enabling farmers to apply the fertilizer that their field needs, in the right amount and at the right time - requires that farmers have “access to knowledge, all needed fertilizers, and related services” (Reetz et al., 2015). In other words, farmers need to know what to apply, they need to be able to get it, and they need to be able to access knowledge and inputs for complementary practices such as improved seeds and organic practices crucial to sustainable use of chemical fertilizers. We see two key reasons why all but a tiny fraction of farmers in Africa do not have this kind of access. One is that, since at least the days of structural adjustment in the 1980s, African governments have dramatically under-invested in rural extension systems and in the soil testing and related agroecological profiling that would allow at least some evidence-based variation in fertilizer recommendations. New technologies promise to reduce the cost of generating improved and spatially disaggregated knowledge of soil characteristics, but these need to be linked to functioning research and extension systems to be put to use for African farmers.

The second key reason that farmers don’t have this kind of access relates to fertilizer and broader agricultural input policy in much of Africa. Private sector fertilizer distribution through markets in principle holds the prospect of providing farmers with greater choice in what they use, but national fertilizer policies frequently undermine these channels (Jayne et al., 2018). Heavy reliance on imported formulations exacerbates this problem, though this is beginning to change due to a large increase in domestic blending of fertilizers.

The bottom line is that moving towards more localized fertilizer recommendations and practice is crucial if Africa’s productivity crisis is to be reversed, and requires greater public investment in data and data systems linked to strengthened rural extension, together with policy and programmatic reform to facilitate a flexible private sector response to farmer input needs.

Deep Localization and “nth-best solutions”

A recurring problem in Africa and many developing countries is the promotion of “showpiece” legislation and programs that mimic what outside experts consider “best practice” but that are never implemented (Pritchett, Wilcock, and Andrews, 2013). Africa must avoid this in its follow-up to the AFSHS. Rather than passively following outside advice, African countries need to marshal their own capacities and use their own processes, as imperfect as they may be, to develop action plans that are put into action, are able to appropriately evolve over time, and are informed by strong, local empirical evidence.

This can happen only through a deeply localized process in which stakeholders are engaged in an iterative process of analysis, design, dialogue, negotiation and bargaining, and redesign. This process – indeed, development of workable policies and program in any country anywhere in the world – is an unavoidably messy social and political process. Empirical scientific input is crucial to good outcomes but is not and cannot be the main driver of what emerges. Indeed, the outcomes that emerge, based on iterative dialogue and political compromise, are typically far from what a researcher would consider “best”. We refer to them as “nth-best solutions”, meaning they are the best available solution given the technical, social, and political dynamics and constraints of the system one is operating in. Far from failure, the development and implementation of such nth-best solutions is a sign of progress in a country’s ability to develop its own approaches that are feasible, “effective enough”, and can be maintained and improved over time.

Attitudes and behavior need to change

We have argued that the follow-up at country level to the AFSHS must involve deep localization, that is, a determination by local stakeholders simultaneously to seek out the best technical advice while subjecting it to the messy bargaining and “deal making” inherent in any authentic design of workable policies and programs that countries can own and take responsibility for. We have further argued that this follow-up must come to terms with Africa’s huge heterogeneity in agroecology, infrastructure, and market access, and generate an approach that allows for hyper localized solutions. These solutions will be possible only through recommendations that are more suitable to farmers’ particular fields combined with greater access by farmers to the knowledge, inputs, and services needed to pursue these recommendations while adapting them based on their own knowledge. Achieving this will require simultaneously increasing public investment and reforming policies and programs to allow greater private sector response to farmer needs through functioning markets.

If African countries are able to do this, we believe they will generate policies and programs that, while far from what might be considered technically “best”, nonetheless stand a far greater chance of being implemented and adapted as needed, to impressive cumulative effect over time.

We suggest that attitudes and behavior by all parties will have to change to make this approach possible. African governments will need to show keener interest in locally generated empirical information even as they promote a highly stakeholder-engaged process of policy and programmatic design that may generate outcomes far from what many consider technically best. Local analysts need to understand and accept the fundamental social and political nature of this process while figuring out how to engage with that process and make their research understandable and relevant to decision makers. The international research community must commit to working in equitable partnerships that involve giving up the right to drive the research agenda. And donors need to recognize that things may take longer working this way and that countable and reportable outputs may be fewer but that outcomes – the changes that matter to people’s lives – should be greater.

Change is hard. Admitting that the way we as a global development community have approached empirically informed policy and programmatic change for many decades needs serious rethinking is especially hard. But by focusing on equitable partnerships and accepting what, on any reasonable reflection, is so obvious – that policies and programs simply must adapt to local political and social realities even while striving to be as effective and efficient and equitable as possible – this change is possible. We know how to proceed – let’s get on with it!

References

Liverpool-Tasie, LSO, B. Omonona, A. Sanou, W. Ogunleye, (2015). “Is Increasing Inorganic Fertilizer Use in Sub-Saharan Africa a Profitable Proposition? Evidence from Nigeria”. Food Policy, 67, 41-51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2016.09.011.

Burke, W., T.S. Jayne, J.R. Black (2017). “Factors explaining the low and variable profitability of fertilizer application to maize in Zambia”. Agricultural Economics, 48(1), 115-126. https://doi.org/10.1111/agec.12299.

Laajaj, R., K. Macours, C. Masso, M. Thuita & B. Vanlauwe (2020). “Reconciling yield gains in agronomic trials with returns under African smallholder conditions”. Scientific Reports, 10, 14286. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-71155-y.

Jayne, T.S., NM Mason, WJ Burke, J Ariga (2018). “Taking stock of Africa's second-generation agricultural input subsidy programs”. Food Policy, 75: 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2018.01.003.

Fixen, P. (2020). “A brief account of the genesis of 4R nutrient stewardship.” Agronomy Journal, 112: 4511-4518. https://doi.org/10.1002/agj2.20315.

Reetz, H., P. Heffer and T. Bruulsema (2015). “4R nutrient stewardship: A global framework for sustainable fertilizer management”, Chapter 4 in Dreschel et al., eds, “Managing Water and Fertilizer for Sustainable Agricultural Intensification”, International Fertilizer Industry Association (IFA), International Water Management Institute (IWMI), International Plant Nutrition Institute (IPNI), and International Potash Institute (IPI). Paris, France, January 2015. ISBN 979-10-92366-02-0.

Pritchett, L., Woolcock, M., & Andrews, M. (2012). “Looking Like a State: Techniques of Persistent Failure in State Capability for Implementation”. The Journal of Development Studies, 49(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2012.709614.

By:

Baboki Gaolaolwe-Major

Monday, Jul 8, 2024

AGRI-FOOD SYSTEMS

+1

Leave a comment

Determinants of Small-Scale Irrigation Use for Poverty Reduction: The Case of Offa Woreda, Wolaita Z

Small-scale irrigation is one of the agricultural activities used by rural farmers to improve the overall livelihood of the rural community by increasing income, securing food, meeting social requirements, and reducing poverty. e main objective of this study was to look into the factors that influence small-scale irrigation for poverty reduction among small-holder farmers in theOffa Woreda, Wolaita Zone.

By:

Elias Bojago

Thursday, Sep 8, 2022

AGRI-FOOD SYSTEMS

+1

Leave a comment

USAID Administrator Samantha Power: A New Vision for Global Development

USAID Administrator Samantha Power delivers remarks outlining a bold vision for the future of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and inclusive development around the world. The speech takes place as USAID celebrates its 60th anniversary. Administrator Samantha Power's remarks will be followed by a conversation with 2020 USAID Payne Fellow Katryna Mahoney

By:

Derek Tobias

Thursday, Nov 4, 2021

AGRI-FOOD SYSTEMS

+5

Leave a comment

Effective Pathways to Africa's Agricultural Transformation

Wednesday, August 4, 20219:30 am –11:00 am ETOnline only

Register: https://primetime.bluejeans.com/a2m/register/qbakxxyw

Agriculture is Africa's primary gateway out of hunger and poverty; the sector employs 65 - 70 percent of Africa's labor force while supporting the livelihoods of 90 percent of the population. However, for the sector to lead the path to the desired food security and superior incomes for Africa, it is imperative that conversations and investments are made towards transforming the continent's agricultural work into a profitable and sustainable enterprise.

The urgency of this transformation has been made clear during the COVID-19 pandemic, where the continent has been forced to re-think its food production and distribution systems. The closure of borders, lockdowns and limitations of movement indicated the need for Africa to develop homegrown solutions for its staple food needs and market development.

It is against this backdrop that this webinar is held as a session to define the investments needed for a vibrant and functional agricultural sector that can deliver sufficient food and nutrition supplies for all as well as exciting farmer incomes. The conversation will address the roles of individual stakeholders, partnerships and leadership in building an inclusive agricultural transformation across the continent. The webinar will also define the role of public sector commitment in transforming the agriculture sector, with notable examples from successes in Rwanda. Similarly, the critical position of private sector participation shall be highlighted as supported by the transformative role of this group in uplifting Ghana's food systems.

This session is facilitated by the Alliance for a Green Revolution on Africa (AGRA), an African-led and Africa-based organization currently leading the pursuit of an agricultural transformation through investments in systems development, policy and state capability, and partnerships. This webinar will feature special opening remarks from Dr. Agnes Kalibata, UN Secretary-General’s Special Envoy to the 2021 Food Systems Summit.

By:

Madeleine Futter

Monday, Aug 16, 2021

WATER, ENERGY, AND THE ENVIRONMENT

No Preview Available

Leave a comment

Join the UCLA African Studies Center and the Earth Rights Institute

Join the UCLA African Studies Center and the Earth Rights Institute

for a virtual forum on climate change in Africa

April 19 – 23, 2021

Registration to attend ARCC (via Zoom) is now open:RSVP here

Students interested in Climate Action Design Thinking Session: Register here

Please join us for this great line-up of four distinguished keynote speakers, thematic panels,

environmental narratives, an exhibitor’s hall, and a design thinking jam session on climate action.

PLEASE SEE UPDATED ARCC FORUM SCHEDULE AND PANELISTS’ BIOS ATTACHED

All times are listed in Pacific Daylight Time (PDT)

(Los Angeles)

UCLA African Studies Center and Earth Rights Institute appreciate the support of the ARCC co-sponsors.

For more information, visithttps://www.international.ucla.edu/asc/article/206676

or email sbreeding@international.ucla.edu or call 323.335.9965.

By:

Madeleine Futter

Monday, Aug 16, 2021

WATER, ENERGY, AND THE ENVIRONMENT

Leave a comment